“The strong are always free by virtue of their superior strength. So long as government is a mere contest as to which of two parties shall rule the other, the weaker must always succumb. And whether the contest be carried on with ballots or bullets, the principle is the same; for under the theory of government now prevailing, the ballot either signifies a bullet, or it signifies nothing. And no one can consistently use a ballot, unless he intends to use a bullet, if the latter should be needed to insure submission to the former.” – Lysander Spooner, No Treason No. 1 Vol. 1, 1867

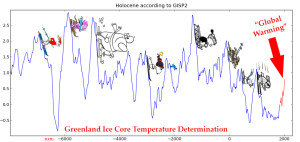

If there is one silver lining to the 2016 presidential election, it’s that it should make abundantly clear to many more individuals that politics is a sham, merely a clownish show where the biggest liars on Earth compete to see who can be the most deceitful while making less of an ass out of themselves than their opponents.

I mean, come on. For a while, it seemed like there might be a battle royale between the House of Clinton and the House of Bush – luckily for us, Jeb Bush had the good sense to drop out early. If only the rest of them had. At the time that I write this, the remaining (noteworthy) candidates are Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton for the Democrats, and Donald Trump and Ted Cruz for the Republicans (Note: This article was written in February 2016).

If anyone but Trump ends up winning, the first Jewish, woman, or Hispanic president will have, at long last, been elected. What a triumph for social justice! And if Trump wins, then we’ll be blessed with the first president who is basically a cartoon character; in fact, back in 2000, The Simpsons predicted that Trump would become president and ruin the country.

It’s incredible that any of these people have made it this far. Bernie Sanders is 74 years old, so perhaps dementia is preventing this self-described socialist from remembering the abject failure of socialist nations around the world, and getting in the way of an understanding of basic economics.

Ted Cruz has been accused of enjoying the music of Nickelback, and he failed to renounce this position when asked. Somehow, this has not derailed his campaign.

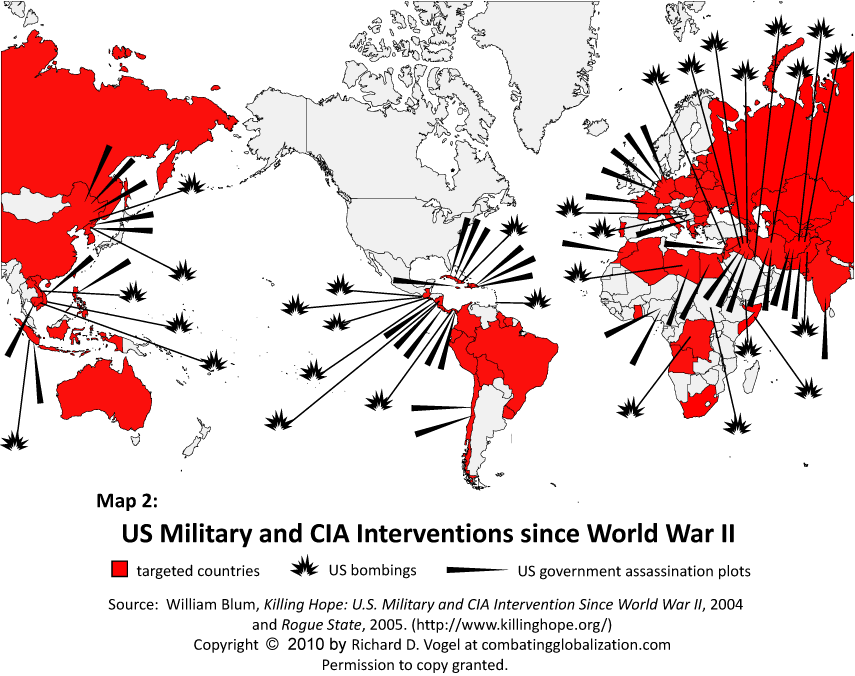

Hillary Clinton is actively under investigation by the FBI for running her own private email server from home while head of the State Department – an immense security issue, if there ever was one. That’s just one of the many controversies surrounding her. Oddly enough, she’s the biggest warmonger of the lot, substantially more interested in military adventures abroad than the Republican front-runners. And she near single-handedly destroyed the country of Libya – the same Libya that has become the major “home away from home” for the Islamic State.

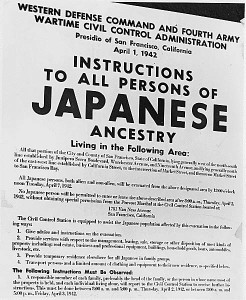

Donald Trump (aka Tronald Dump) has said so many boneheaded things that he hardly requires introduction. If anyone were to bring back internment camps, such as those used to house Japanese-Americans during World War 2, it’d be him. Don’t think it won’t happen again.

One of these dipshits will almost certainly become the next POTUS. And unlike many of you, I will have nothing to do with it. For you see, I have elected not to vote. In this post, I hope to convince you to do the same.

Your Vote Is Meaningless

I hate to break it to you, but your vote is meaningless. This is simply the reality, and there is no use in trying to deny it.

First of all, your vote has a truly negligible chance of swaying an election (and as the population increases, this chance becomes worse and worse with every election). But even if, mathematically speaking, your vote were to be the “deciding” one, the election would ultimately be decided in some shady, back-room deals. Worse still, that doesn’t even matter, since you elect politicians who have no obligation to abide by their campaign promises, and are far more likely to be swayed by their corporate cronies than by “the will of the people.” Besides, the candidates are nearly identical in most important ways, so it’s as though you had no choice at all.

This narrative conflicts with most peoples’ utopian views of democracy and its value. This doesn’t make it any less true. Your vote simply will not decide an election, as I’ve said before:

“In order for your vote to determine anything, the outcome of the election (excluding yourself) would need to either be a tie, or have a one vote difference, with your vote being for the candidate who was losing (thus making it a tie).

The chances of this happening in a national election are negligible, and for other elections, still miniscule. For instance, take a look at this list of close elections throughout the world. There were a handful of ties or elections determined by a single vote, but nearly all of these were more local elections within sparsely populated Canadian territories. Every one of these elections had less than 40,000 total votes cast, most with well under 10,000.”

Even the most optimistic of academic estimates that your vote will be the deciding factor in a national election are between 1 in 10 million and 1 in 100 million depending on the state you live in. The mathematics of voting are so clear that it is hardly worth belaboring the point, but I do want to say that you are literally more likely to die on your way to the polling station on election day than to have your vote matter (and for more on the math, see this).

But even in the unlikely event that your vote almost makes a difference, it still simply won’t matter. There’s no need for “kooky” conspiracy theories to see this. Consider the close call in Florida in 2000. Multiple recounts occurred, none of which ended in a tie. And the process, of course, got shadier and shadier as the counting went on. And now that we have electronic voting machines, there are many reasons to be skeptical of the integrity of elections. Voting machines that have been used in real life elections are highly susceptible to hacking and having votes changed. There is statistical evidence that voting machines have been tampered with and had vote counts changed across numerous election cycles. For more on how crappy electronic voting is, see Ross Anderson’s “Security Engineering”, section 23.5 (free PDF). Among many examples provided in that section:

“Many problems were reported in the 2002 elections [551]; then, the following summer, the leading voting-machine supplier Diebold left its voting system files on an open web site, a stunning security lapse. Avi Rubin and colleagues at Johns Hopkins trawled through them found that the equipment was far below even minimal standards of security expected in other contexts. Voters could cast unlimited votes, insiders could identify voters, and outsiders could also hack the system [731]. Almost on cue, Diebold CEO Walden O’Dell, who was active in the campaign to re-elect President Bush, and wrote ‘I am committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year’ [1320].”

It’s not as though voting fraud is unheard of; it became significant under Lincoln and during the “Reconstruction”.

“Lincoln was known to instruct his military commanders to furlough registered Republicans while keeping Democrats (and any others) in the field, where they could not vote. In border states like Maryland, where there was powerful opposition to the war, federal soldiers flooded the cities on election days and were instructed to vote, even though they were not residents of those states.”

…

“Almost all Southern males were disenfranchised, while virtually all of the male ex-slaves were registered to vote (Republican). No Southern male could vote who participated in the war effort in any way, including contributing food or clothing to the Confederate army. Voter registration required one to publicly proclaim that one was on the side of the federal armies during the war, something that no sane southerner who valued his life would do.”

Today, a well-known problem is gerrymandering, or creating odd borders for districts to sway elections based on known voter demographics. This stuff is common. Plus, as Robert Epstein showed in a brilliant essay, big tech companies like Google and Facebook have the power to sway elections by changing what we are exposed to, and we would never know. Do you think these big companies are looking out for the “public interest” or their bottom lines? Research shows that big business and special interests are the real factor that influences government policy, as I’ve stated in the past:

“…the most robust of modern research on the topic has concluded that even mass groups of voters have a minimal effect on public policy. Rather, it is interest groups and powerful business interests that control policy outcomes. How else would incumbents win in Congressional elections over 90% of the time, even in a year like 2010 where people were particularly unsatisfied with their representatives?”

Whoever wins the election – even in the off chance that they are truly public spirited, Leslie Knope-esque individuals – will be forced by their position to adjust their policies to conform to the whims of those powerful interests. Perhaps this is part of the reason why the two major candidates are nearly identical on most major issues, making the whole election an absurd political circus. As Jesse Ventura said of our two-party system,

“[W]hat you have today is like walking into the grocery store and you go to the soft drink department, and there is only Pepsi and Coke. Those are the two you get to choose from. There is no Mountain Dew, no Root Beer, no Orange. They’re both Colas; one is slightly sweeter than the other, depending on which side of the aisle you are on.”

Why Politicians Act Like Scumbags

“What is any political campaign save a concerted effort to turn out a set of politicians who are admittedly bad and put in a set who are thought to be better. The former assumption, I believe is always sound; the latter is just as certainly false. For if experience teaches us anything at all it teaches us this: that a good politician, under democracy, is quite as unthinkable as an honest burglar.” – H.L. Mencken

Your vote is meaningless, and politicians know this. And voting is a fundamentally different process than that of market forces, which leads to predictable behavior on the part of politicians, as documented by Mark Brandly.

Consider how the free market works: in the market, consumers decide exactly what they want to buy. Each consumer can buy completely different things and there is no reason for conflict, because my buying a blue shirt doesn’t impose the blue shirt on you, and you buying a red shirt doesn’t impose that red shirt on me. Each consumer can get whatever he wants, and doesn’t get anything he would prefer not to have. Each consumer has an incentive to be informed about the products he is buying, because he is spending his own money on them. Researching the possible items, particularly big ticket items, makes an actual difference in a consumer’s life. None of this is true in the political “market”.

“Choosing between two candidates is analogous going to Walmart and being presented with two shopping carts already filled with items. Everyone will leave the store with the same cart of goods. Each cart contains products that a person may want and products that one wouldn’t choose to have, but the voter is not able to take anything out of either cart.”

…

Also…the two carts are very similar. They contain many of the same items, the items that are different are still similar (e.g., both carts contain a shirt — one red and one blue), and the two carts cost about the same amount. In addition, each taxpayer will end up paying for one of the carts even though he wouldn’t voluntarily purchase this basket of items.

…

…when you are presented with the two carts, you are allowed to vote on which cart you want. However, you vote infrequently, say, once every four years, and your vote doesn’t matter. You will end up with the same cart regardless of your vote. In fact, even if you don’t vote, this will not affect the bundle that you receive in your cart.”

Democracy is even worse than this analogy suggests. A candidate can promise certain policies and completely renege on them when elected. With the shopping cart, you at least know that if something is in there, it’s in there. So how does the structure of political democracy encourage politicians to misbehave?

“The point, so far, is that in an election voters are faced with bundled choices, they vote infrequently, no individual’s vote will affect the election, voters have little incentive to be highly informed about the candidates’ policy positions, and the winning candidate is not obliged to deliver on his promises. Candidates who understand these simple facts about an election will have an advantage over political opponents who do not understand the nature of elections.

Realizing this, candidates need to make two important decisions. First, a candidate must consider which bundle of policies will give him the best chance of winning the election, and second, a candidate must devise a strategy that will give his supporters an incentive to vote in spite of the fact that no individual vote matters.”

First, candidates will tend to pick positions that are more centrist in order to appeal to the bulk of voters, who cluster around less “extreme” views. This means that both candidates will have very similar policies.

“The last two presidential administrations demonstrate this point. Even though they represent different political parties, many of the foreign-policy and financial advisors of the Bush administration would be comfortable in the Obama administration and in some cases the same individuals are in both administrations. Bush and Obama both support the welfare state and the military empire. They both have proposed budgets greatly expanding the budgetary size and legal reach of our federal government.”

This means that candidates are inclined to deceive the public about their positions in order to appeal to this median voter. But it’s a little bit more complicated than that.

“In order to gain political power in our system, a candidate must win two elections, the primary election and the general election. The difficulty for a candidate is that he needs to appeal to a different set of voters in each election. In order to win the primary election, a candidate must attract the median voter of his party’s primary voters. Then the candidate must change his position to gain the support of the median voter in the general election.”

This is tricky, but there are some strategies that politicians can employ to make this easier. Two keys to winning include being the first to accuse your opponent of flip-flopping, and buying favors with government power. These favors should have the costs dispersed among as many people as possible, but the benefits accruing to smaller groups of rent seekers who are more likely to organize on your behalf. You can also hide the costs, as in the Social Security system, where half of the tax is paid by the employer, even though that cost is ultimately borne by the employee anyways. Basically, candidates have strong incentives to lie to the voters. Candidates who are averse to being deceitful are at a huge disadvantage in an election.

“…a candidate will never claim that his main goal is to acquire political power so that he can enrich himself. He will use pet phrases that hide the true nature of his policies. No matter what policy he is defending, he may claim that the program is “for the children,” or that it will “strengthen the family.” Other possibilities include asserting that the policies will “grow the economy” or “help the environment.” In the current political atmosphere, saying that you are “fighting terrorism” will blind many people to your actual intent. The point is that simple platitudes will fool many people.

…

Another lie we hear is candidates’ assertion that (even though they would take similar positions when in office) there are major differences between them. Each will claim that their policies will lead to prosperity and security, and that their opponent’s positions will result in impoverishment and ruin. Convincing supporters that there is a major difference between the candidates will make it more likely that they will vote. A candidate needs to continually push his supporters to go to the polls.

A common tactic for gaining support is fear mongering. Fear often trumps logic. Voters can be scared into believing that there will be dire consequences if their candidate loses the election. A candidate can appeal to his followers by claiming that if the other candidate wins the election we will be attacked by terrorists, or our taxes will be raised, or we may lose our jobs, or our children will not get a good education, or we will run out of oil, or we may not get adequate health care, or the environment will be destroyed. While some of these claims may be correct, they are true regardless of which candidate wins the election, because either winning candidate will implement policies that will do us much harm. In making such claims, candidates rely on the fact that voters will not recognize that the candidates largely agree on the major issues regarding government policy.”

This also explains why politics tends to be so negative, and attack ads are used so frequently despite people generally being “against” them. Ultimately, this just leads to divisiveness and conflict.

“Selling your product in the private sector requires a customer to cast an affirmative vote to buy it. Just convincing a potential customer that a rival product should not be purchased does not mean a sale for you.

This is because a sales prospect can choose from among several sellers, or he can choose to not buy at all. But those options are unavailable in an election with only two major parties, where customers are effectively forced to “buy” from one of them.

In an essentially two-party election, convincing an uncommitted voter to vote against the “other guy” by tearing the opponent’s position down is as valuable to a candidate as convincing that voter of positive reasons to vote for him; either brings him a vote closer to a majority. That is not true in the private sector, as only votes for you–purchases–help you.

Similarly, talking a voter committed to a rival to switch to your side is worth two votes, since it adds one to your vote column and subtracts one from your rival’s. But you would only benefit from the single additional purchase/vote for you in the private sector. Further, in an election, finding a way to get someone who would have voted for your rival to not vote at all is as valuable as getting one more voter to vote for you.

This is why negative campaigns that turn voters off from political participation altogether are acceptable in politics, as long as a candidate thinks he will keep more of his competitor’s voters away from the polls than he will his own. In the private sector, such an approach would not be taken, as it would reduce, rather than increase, sales.“

I suspect that most people intuitively understand how messed up this all is, but have resigned that this is simply the way things are.

““Well, that’s the way the game is played,” I sometimes hear. “If you don’t fight dirty, you aren’t going to win, so even the good ones have to fight dirty. An honest candidate couldn’t win.” But if you have accidentally (let us hope) established a political system that excels at elevating psychopaths to positions of power and authority, maybe the answer is not to hope for a flock of honorable people who can impersonate psychopaths long enough to climb into power, but to stop propping up a process that installs psychopaths as your rulers, and, once these psychopaths have been successfully identified by their success in the electoral process, to stop giving them so much power to do evil.” – David Gross

The Ethics of Voting

“The state — or, to make the matter more concrete, the government — consists of a gang of men exactly like you and me. They have, taking one with another, no special talent for the business of government; they have only a talent for getting and holding office. Their principal device to that end is to search out groups who pant and pine for something they can’t get and to promise to give it to them. Nine times out of ten that promise is worth nothing. The tenth time is made good by looting A to satisfy B. In other words, government is a broker in pillage, and every election is sort of an advance auction sale of stolen goods.” – H.L. Mencken

You may or may not believe that voting is a decision in the realm of ethics, but there are serious moral considerations involved with the decision to vote or not. Most people do not fully consider the moral ramifications of the act of voting.

It helps to first consider what government is in the first place. A commonly accepted definition offered by famed sociologist Max Weber is that government is an institution that holds a monopoly on the legitimated use of force in a geographic area. While I would dispute the notion that governments’ use of force is in fact morally legitimate, I cannot deny that the force of government at least seems legitimate to most people. What this means is that, while you or I are not allowed to steal from each other, the government can steal from us (“taxation”). And while you and I are not allowed to kidnap people for behaving in ways that we don’t agree with, the government can imprison people for engaging in officially prohibited behaviors.

This is important. When a new law is created, that means a new instance of institutionalized violence has been born. Real people will be stolen from (“fined”, “taxed”) or sent to jail because of it. Even if nobody is directly stolen from or imprisoned, the law creates a threat of violence, which isn’t that much better.

When seen in this light – whether you view the law or government as legitimate or not – the moral implications of voting become somewhat more clear. If you vote for a political candidate and that person then helps to create or enforce laws, then you are in part responsible for the violence that ensues. Stated differently (emphasis mine):

“Voting is an act of consent…When you vote you agree to abide by the rules of the game and accept the outcome. By voting, the voter endorses the governmental system under which he or she lives and those in control of it. Each voter is saying: It is right and proper for some people, acting in the name of the State, to pass laws and to use violence to compel obedience to those laws if they are not obeyed regardless of the morality of those laws.”

Note the crucially important clause “regardless of the morality of those laws.” If you vote, and then your government starts aggressive foreign wars, kills people without due process in drone strikes, imprisons nonviolent drug users, etc., then you have consented to and encouraged this needless violence. You are in part morally responsible for acts of violence done by an agent operating on your behalf (government) despite almost certainly never being willing to commit comparable acts of violence directly.

In this way, and many others, politics turns us into worse human beings.

“…politics doesn’t just make the world around us worse. It makes us worse, as well. When we participate in politics—by seeking office, by voting—we take part in a system where we attempt to decide for others while they attempt to decide for us, and where those decisions, whoever makes them, are backed by violence or, at the very least, the threat of violence. It’s a system where the participants say to each other, “I know what’s best for you, you need to do what I say, and if you don’t, these men with guns will threaten you or take your money or lock you in a cage or kill you.” Such a system encourages us to deal with each other in ways beneath the standards of behavior we ought to reach for, and it encourages us to see each other not as friends and companions and fellow seekers of the good life, but as enemies and rivals and obstacles in the way of finding happiness.

Politics inculcates pettiness, short-sightedness, Manichean thinking, tribal feuds, selfishness, and rage. It discourages reason and respect and a basic appreciation of the dignity of others, especially those who seek lives different from our own. It makes us less likely to find virtuous mentors or learn from the virtuous actions of others, because everyone we encounter will themselves suffer from its corrosive influence. Politics encourages extreme reactions instead of careful seeking of the proper, measured response. Politics distances decisions from local knowledge and so limits moral wisdom by making it less likely we will act to bring about virtuous outcomes even when motivated by virtuous impulses.”

The violence of government and the nature of democracy do bring up an interesting question though: can we vote in self-defense? After all, while we don’t normally condone shooting innocents, most people agree that it is okay to shoot someone who is shooting at you. In the same way, can we vote in order to counteract people who are voting “at” us?

Reasonable people can disagree on this question. For specific referendums on political questions, I believe the answer is yes, you can vote in self-defense. Usually, this means voting “no” to prevent some sort of aggression, but in rare circumstances, you may be able to vote “yes” to remove an existing aggression. For instance, I believe that you can vote to decriminalize drugs, prostitution, or other victimless crimes.

But what about elections for politicians? Is it self-defense to vote for “the lesser of two evils”? Libertarian Wendy McElroy tackles this question:

“But a libertarian senator would be a lesser evil, it is argued. He would be a good politician. Nonsense. It is not the particular man that is objectionable; it is the position of power itself. Moreover, a successful libertarian politician would take an oath to uphold massively unjust laws. Either he would be lying then or he would have been lying beforehand when he claimed to be libertarian. In either case, he is another lying politician.”

More theoretically,

“Voters defend themselves against a politician who would be more draconian than the candidate they favor. Instead of firing a bullet in self-defense, they fire a ballot to knock out worst alternatives. The problem is that a defensive bullet can be narrowly aimed at a deserving target. A ballot attacks innocent third parties who must endure the consequences of whichever politician is assisted into a position of unjust power. Innocent people will bear the brunt not only of government actions but also of being robbed to pay for them. Every voter bears moral responsibility for this injustice.”

Voting, therefore, is not analogous to other instances of self-defense. If someone were shooting at you, voting would be like shooting back at them – and all of the other people in the room. Obviously, voting does not have the same moral intensity as shooting people, but it is still immoral.

Reasons To Vote, Debunked

Despite the moral and practical reasons not to vote, countless platitudes are trotted out each election season in order to encourage people to vote. Most are just ridiculous appeals to “patriotism”. Some are mentioned so frequently and yet are so patently absurd that they need to be addressed individually.

“If you don’t vote, you have no right to complain.”

This is one of the stupidest things I’ve ever heard, and it should only take a moment of thought to understand why. George Carlin does a great job of explaining it at around 2:10 into this video:

I hope that when people use this excuse for voting, they do not quite mean it literally – after all, everyone has a right to complain. That’s freedom of speech. Perhaps they mean that those who participate in some enterprise have a more legitimate grievance when things aren’t going well.

“In his 1851 book Social Statics, the English radical Herbert Spencer neatly describes the rhetorical jujitsu surrounding voting, consent, and complaint, then demolishes the argument. Say a man votes and his candidate wins. The voter is then “understood to have assented” to the acts of his representative. But what if he voted for the other guy? Well, then, the argument goes, “by taking part in such an election, he tacitly agreed to abide by the decision of the majority.” And what if he abstained? “Why then he cannot justly complain…seeing that he made no protest.” Spencer tidily sums up: “Curiously enough, it seems that he gave his consent in whatever way he acted—whether he said yes, whether he said no, or whether he remained neuter! A rather awkward doctrine this.””

By making the argument that not voting waives your right to complain, you essentially argue that nobody has a right to complain in the political realm! If anything, it is far more intuitive to assert that the act of voting forfeits your right to complain in the way that both George Carlin and Herbert Spencer mentioned above – you have provided consent to the system by voting. Don’t get me wrong though, everyone has a right to complain and should complain about politicians at every available opportunity. But the act of voting makes your opinion matter just a little bit less.

“People have sacrificed their lives for your right to vote!”

This is another curious one, considering how no major war was ever fought defending your right to vote. America has even lost some wars, but this hasn’t stopped voters. After Saigon fell in 1975, how have we managed to elect politicians since?

It’s even sillier to make this claim in light of the defeats during the 1930s of the Ludlow Amendment, a proposed constitutional amendment that would have required a national referendum in order to declare war, except when attacked first. Despite massive public support (75% of the population supported it), it was unable to gain traction in Congress and died in committee. I suspect that if enacted, this amendment would have made little difference (for instance, the US would still have entered Vietnam despite the Gulf of Tonkin incident being completely fabricated). That being said, how can we say that people have fought for our right to vote when we don’t even have a right to vote on the wars that they fight in?

And surely, even if people had died defending the right to vote, they would have supported the right to abstain as well. Especially if all of the options for who to support are evil.

“Vote for the lesser of two evils.”

There is so much that is wrong with this “advice” that it makes me recoil a little bit when people recommend to “vote for the lesser of the two evils.” Imagine you are confronted with the following choice:

- Endorse murder

- Endorse rape

- Abstain from endorsing either.

Clearly, we ought to abstain. But the person who suggests voting for the lesser evil may respond in this absurd, self-righteous way: “Oh, you don’t vote? Well I guess that means you would let murder win! I, on the other hand, support rape, the lesser of the two evils!”

When you vote for any evil, you are in part responsible for the evils that are then committed on your behalf. And if being evil doesn’t stop politicians from being elected by voters, then the quality of candidates will continuously degrade as they realize that they can get away with whatever they want.

I love the way Frank Chodorov frames this in his book Out of Step.

“Particularly was I impressed by the candidates’ evaluations of one another. Neither one had a good word to say of his opponent, and each was of the opinion that the other fellow was not the kind of man to whom the affairs of state could be safely entrusted. Now, I reasoned, these fellows were politicians, and as such should be better acquainted with their respective qualifications for office than I could be; it was their business to know such things. Therefore, I had to believe candidate A when he said that candidate B was untrustworthy, as I had to believe candidate B when he said the same of candidate A. In the circumstances, how could I vote for either? Judging by their respective evaluations of each other’s qualifications I was bound to make the wrong decision whichever way I voted.

…

Admitting that there is no difference in the political philosophies of the contending candidates, should I not choose the “lesser of two evils?” But, which of the two qualifies? If my man prevails, then those who voted against him are loaded down with the “greater evil,” while if my man loses, then it is they who have chosen the “lesser evil.” Voting for the “lesser of two evils” makes no sense, for it is only a matter of opinion as to which is the lesser. Usually, such a decision is based on prejudice, not on principle. Besides, why should I compromise with evil?

If I were to vote for the “lesser of two evils” I would in fact be subscribing to whatever that “evil” does in office. He could claim a mandate for his official acts, a sort of blank check, with my signature, into which he could enter his performances. My vote is indeed a moral sanction, upon which the official depends for support of his acts, and without which he would feel rather naked.”

Again, voting has ethical ramifications. When you vote for a candidate, you are not voting for a reduction of evil, but rather a continuation of it.

“Vote! It’s your civic duty.”

To be honest, I’m not exactly sure what this means. I suspect that most people who use this platitude do not understand what they are saying either. Presumably, we must vote in order to be considered a “good citizen.” Unfortunately, elevating the importance of elections in this way tends to encourage people to conceive of these elected offices as ones that ought to hold great power.

“Those who exaggerate the importance of elections (usually as part of their campaign pitch about how important it is for you to vote, and in a particular way) also tend to exaggerate the power of office-holders and the abilities (and propensities) of the politicians who hold office. This has the unfortunate effect of getting people accustomed to the idea that these offices ought to have great powers concentrated in them, and ought to be looked on to solve our problems, create miracles, provide for our needs, and so forth. This in turn makes the psychopaths in power more dangerous.”

It not only makes those in power more dangerous, but it also makes your fellow citizens into dangerous enemies to be vanquished, rather than merely individuals with whom we have a difference of opinion. Politics and voting are not your “civic duty” – rather, they are an institutionalized mechanism which causes social chaos and divisiveness among good people.

“It’s not difficult to understand why politics plays such a central role in our lives: political decision-making increasingly determines so much of what we do and how we’re permitted to do it. We vote on what our children will learn in school and how they will be taught. We vote on what people are allowed to drink, smoke, and eat. We vote on which people are allowed to marry those they love. In such crucial life decisions, as well as countless others, we have given politics a substantial impact on the direction of our lives. No wonder it’s so important to so many people.

…

Politics takes a continuum of possibilities and turns it into a small group of discrete outcomes, often just two. Either this guy gets elected, or that guy does. Either a given policy becomes law or it doesn’t. As a result, political choices matter greatly to those most affected. An electoral loss is the loss of a possibility. These black and white choices mean politics will often manufacture problems that previously didn’t exist, such as the “problem” of whether we—as a community, as a nation—will teach children creation or evolution.”

These disagreements are a waste of time, and could easily be resolved by allowing voluntary communities to determine their own rules on such matters. Instead, these disagreements are elevated to a battle between Good and Evil, Virtue and Vice.

“What’s troubling about politics from a moral perspective is not that it encourages group mentalities, for a great many other activities encourage similar group thinking without raising significant moral concerns. Rather, it’s the way politics interacts with group mentalities, creating negative feedback leading directly to viciousness. Politics, all too often, makes us hate each other. Politics encourages us to behave toward each other in ways that, were they to occur in a different context, would repel us. No truly virtuous person ought to behave as politics so often makes us act.”

So no, voting is not your civic duty. No reasonable definition of a civic duty can require us to engage in behaviors that create a social war of all against all. If anything, you have a duty to abstain from voting in order to avoid fostering additional conflict.

“Voting is a way to speak your mind and let your voice be heard!”

“Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” – H.L. Mencken

“When a candidate for public office faces the voters he does not face men of sense; he faces a mob of men whose chief distinguishing mark is the fact that they are quite incapable of weighing ideas, or even of comprehending any save the most elemental — men whose whole thinking is done in terms of emotion, and whose dominant emotion is dread of what they cannot understand. So confronted, the candidate must either bark with the pack or be lost… All the odds are on the man who is, intrinsically, the most devious and mediocre — the man who can most adeptly disperse the notion that his mind is a virtual vacuum. The Presidency tends, year by year, to go to such men. As democracy is perfected, the office represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.” – H.L. Mencken

Or, a closely related slogan: “vote for change!” For some reason, this last one seems to work best on the young and ignorant; I recall the 2008 election where the majority of this demographic almost religiously got in line behind Obama, leading to creepy things like this song, “I believe in Barack Obama” by the Hush Sound.

Despite Obama doing things just about the same as Bush did, this same demographic has overwhelmingly been supporting Bernie Sanders with the same vigor. I suspect that if Bernie is elected, we’ll have about the same amount of “change”.

But by far the “best” variant on the “let your voice be heard!” argument is one that I read on this handout from an organization called the Partnership for Safety and Justice (emphasis in original):

“Last but not least, because it gives you credibility! Often times, we voice our concerns to elected officials, but if we aren’t voting, our concerns may not matter at all to them. Voting can actually give you the credibility to make your concerns a top priority for legislators.”

Read that again. Apparently, your vote captures your opinions about how the country should be run and the politicians are listening to you! Oh, come on now. As discussed above, your vote is meaningless, your concerns actually don’t matter at all to politicians – not when there are special interests to please.

In the market, there are ways to “let your voice be heard” that do not involve forcing your opinions on others. Voting can even be a decent method for this, such as members of an organization voting on proposed rules, or a group of friends voting on where to go for dinner. Voting in political elections is nothing like this.

“So what do I mean by “politics?” I mean the act of deciding for others via the mechanisms of the state. Choosing for others, and then getting government to make them go along with our choices. Granted, when we make decisions via those mechanisms—by, say, voting—we expect the outcome will apply to ourselves and not just to other people. But it’s misleading to say we are “deciding for ourselves” when we vote, because if what we vote for is something we would’ve done anyway, we could always choose to do it independent of a vote. If I think contributing money to a cause is worthwhile, I don’t need the state to make me do it. I can cut a check any time. By voting, by shifting from the personal and voluntary to the political and compulsory, we call for the application of force. A vote is the majority compelling the minority to comply with the majority’s wishes. Thus politics is a method of decision-making where choices are moved from individuals choosing privately to groups choosing collectively, and where the decisions those groups arrive at are backed by law and regulation. It’s this last aspect—the backing by the force of law—that distinguishes politics from, say, five friends voting on where to go for dinner.”

Contrary to what many say, voting is not a way to voice your opinion. It is a way to legitimize the rule of others. Two brief stories will help drive this point home. First, consider Wendy McElroy’s recitation of a parable by Larken Rose:

“The anarchist Larken Rose presented a realistic view of slaves voting in his parable, “The Jones Plantation.” Slave-owner Jones laments to slave-owner Smith about risking the disobedience of his slaves by pressing them to work harder. Smith offers a solution. He gathers the slaves and declares them to be free men who will work for themselves henceforth. He advises them to stay on the plantation, however, as slave-owning neighbors would recapture them immediately. He adds: Since only Jones has experience in running a plantation, Jones will remain as administrator. The ‘former’ slaves go to work in the cotton fields with the renewed vigor of free men.

The next day, a handful of ‘former’ slaves become supervisors to ensure the rules are followed in order “to benefit all equally.” The rest work with renewed vigor.

On day three, a man named Samuel is whipped for holding back some cotton for his own use; this is called “stealing” from everyone else. When Samuel complains there is no difference between freedom and slavery as long as Jones makes all the rules, Smith gathers the ‘former’ slaves and tells them there will be an election every three months in which either Jones or Jones’s cousin will be voted administrator; the ‘former’ slaves are in control. Moreover, everyone now has two minutes in which to speak out at each gathering.

Eventually, Samuel uses his two minutes to say that nothing has changed. Jones and his cousin are exactly the same; they take the wealth and leave next to nothing for the ‘former’ slaves. The other workers turn against Samuel.

Rose presents some of the key elements of voting, especially in the context of slavery. Voting provides an illusion of freedom, a delusion of control to which the slaves cling. It turns them against each other both as supervisors and as workers who are either pro-Jones or pro-cousin. It turns the slaves against the one man who speaks the truth in protest. And nothing, nothing about the conditions of slavery change…except the words describing it. Voting is called “freedom,” “democracy,” “civic responsibility,” or “self-defense.”“

Voting gives the masses a sense as though they have some control or freedom, but this is just an illusion.

A similar parable is Robert Nozick’s “Tale of the Slave”, from his award winning book Anarchy, State, and Utopia.

“Consider the following sequence of cases… and imagine it is about you.

- There is a slave completely at the mercy of his brutal master’s whims. He often is cruelly beaten, called out in the middle of the night, and so on.

- The master is kindlier and beats the slave only for stated infractions of his rules (not fulfilling the work quota, and so on). He gives the slave some free time.

- The master has a group of slaves, and he decides how things are to be allocated among them on nice grounds, taking into account their needs, merit, and so on.

- The master allows his slaves four days on their own and requires them to work only three days a week on his land. The rest of the time is their own.

- The master allows his slaves to go off and work in the city (or anywhere they wish) for wages. He requires only that they send back to him three-sevenths of their wages. He also retains the power to recall them to the plantation if some emergency threatens his land; and to raise or lower the three-sevenths amount required to be turned over to him. He further retains the right to restrict the slaves from participating in certain dangerous activities that threaten his financial return, for example, mountain climbing, cigarette smoking.

- The master allows all of his 10,000 slaves, except you, to vote, and the joint decision is made by all of them. There is open discussion, and so forth, among them, and they have the power to determine to what uses to put whatever percentage of your (and their) earnings they decide to take; what activities legitimately may be forbidden to you, and so on.

- Though still not having the vote, you are at liberty (and are given the right) to enter into the discussions of the 10,000, to try to persuade them to adopt various policies and to treat you and themselves in a certain way. They then go off to vote to decide upon policies covering the vast range of their powers.

- In appreciation of your useful contributions to discussion, the 10,000 allow you to vote if they are deadlocked; they commit themselves to this procedure. After the discussion you mark your vote on a slip of paper, and they go off and vote. In the eventuality that they divide evenly on some issue, 5,000 for and 5,000 against, they look at your ballot and count it in. This has never yet happened; they have never yet had occasion to open your ballot. (A single master also might commit himself to letting his slave decide any issue concerning him about which he, the master, was absolutely indifferent.)

- They throw your vote in with theirs. If they are exactly tied your vote carries the issue. Otherwise it makes no difference to the electoral outcome.

The question is: which transition from case 1 to case 9 made it no longer the tale of a slave?”

Conclusion

I don’t expect this essay to convince many. Those who believe that one “should” vote are unlikely to be pursuaded by reason. But hopefully I have at least planted the seed of understanding in some readers, such that one day, upon becoming fed up with the political process, they will awaken to the idea that perhaps participating in this charade is a waste of time.

The politicians and the democratic process that legitimizes their power will chug along just fine without you. As Frank Chodorov remarked,

“All in all, I see no good reason for voting and have refrained from doing so for about a half-century. During that time, my more conscientious compatriots (including, principally, the professional politicians and their ward heelers) have conveniently provided me with presidents and with governments, all of whom have run the political affairs of the country as they should be run — that is, for the benefit of the politicians.

…

Why should any self-respecting citizen endorse an institution grounded on thievery? For that is what one does when one votes. If it be argued that we must let bygones be bygones, see what can be done toward cleaning up the institution of the State so that it might be useful in the maintenance of orderly existence, the answer is that it cannot be done; you cannot clean up a brothel and yet leave the business intact. We have been voting for one “good government” after another, and what have we got?”

For those of you who vote despite this, I agree with George Carlin’s sarcastic quip: I’m sure that the country will improve dramatically after your guy gets elected.